[NOTE: This post has been updated to correct several errors. Thanks to my colleagues, Larry Canale and Keith Gentili, for correcting the record.]

For a time in the 1990s, I was the publisher of Tuff Stuff, a magazine for collectors of sports trading cards and memorabilia. (In the collectibles hobby, “tuff stuff” is the term for a rare find.) Each year, we sent a large contingent to the biggest gathering of sports collectors in the U.S., a show called “The National.” The event brought together thousands of hobbyists, hundreds of trading card and memorabilia dealers, and all the major card companies from Topps to Upper Deck.

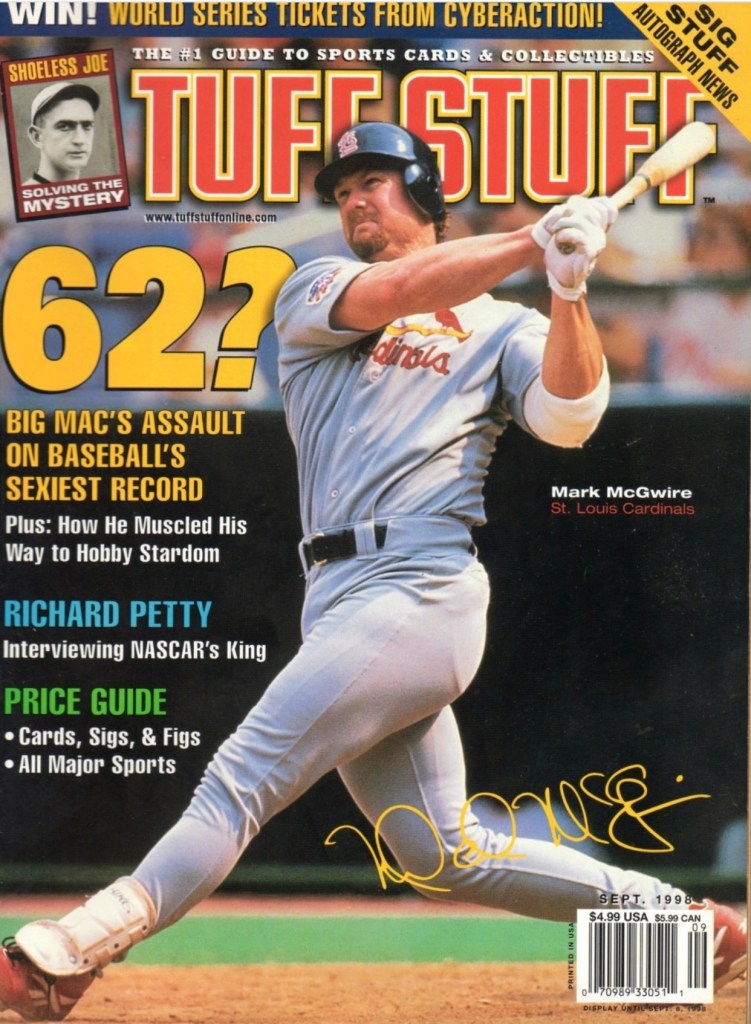

The 1998 National was held in Chicago that summer. Tuff Stuff rented a large booth in a prime location. We planned to distribute copies of our September issue featuring Mark McGwire on the cover. The St. Louis Cardinals slugger was bashing his way to a record-breaking 70 home runs that season.

For each sports star we featured on our cover, we printed a facsimile of his autograph. So there on the cover of Tuff Stuff was McGwire’s autograph.

On the opening day of the National, I was standing in our booth when a middle-aged man in his forties approached and introduced himself.

“I’m Gary Brison,” he said. “I’m a memorabilia dealer and I also represent Mark McGuire to the sports collectibles industry.” As he presented his card, I half expected him to say how much he liked our cover. He did not. Instead, he dropped a bombshell.

The autograph on the cover of your magazine is a fake.”

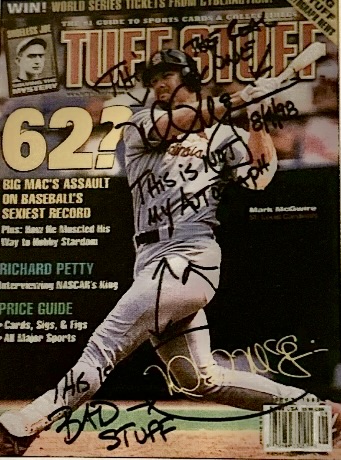

“I’m here to tell you that the autograph on the cover of your magazine is a fake,” he said. “You are misleading collectors as to what a genuine Mark McGwire autograph looks like, so my client insists that you remove it from circulation.” Brison had seen McGwire the day before and showed me a copy of the cover that the slugger himself had marked up. There was his signature in bold black ink. “This is the real one,” he’d written above his autograph with arrows pointing to it. Below that, McGwire had circled the facsimile and written, “This is not my autograph.” To cap it off, he had written “This is BAD stuff.” Ouch!

I don’t remember my exact words, but I asked Gary to give me time to consult with my team. “Come back in an hour,” I said.

I huddled with the editors and started asking questions. Where did we get the McGwire autograph? Normally, we obtained samples from reputable collectibles dealers who trade in autographed memorabilia. That was how we sourced the now-questionable McGwire signature.

What about Gary? Was he for real? I didn’t know him, but we confirmed with other industry people that he was, in fact, McGwire’s collectibles representative.

What about the autograph? Was it really a fake? The dealer we got it from was reputable, my staff said. In the end, I decided that was irrelevant. We couldn’t very well challenge Gary’s word that the facsimile was a phony, especially when McGwire himself had said so. We had no choice but to accept the claim.

But when it came to removing the issue from circulation, that was flat out impossible. The September Tuff Stuff had already been mailed to subscribers. It had shipped to newsstands nationwide, and copies were on the way to hobby shops, too. The only copies still under our control were the ones we were handing out at the National.

When Gary returned an hour later, I explained why we couldn’t take the magazine out of circulation. But I laid out the plan my team had come up with: First, we would cross out McGwire’s autograph on the covers off the issues we were handing out at the National. Second, we would insert a press release in each copy alerting readers at the show about the error. Third, we would print an editorial correction in the October issue about the problem. And finally, we would distribute that same press release to reporters covering the National to publicize the fake autograph on our cover.

Fortunately, Gary proved to be a reasonable man. He accepted our plan.

While the Tuff Stuff staff began crossing out McGwire’s autograph on copies of the magazine, I hustled to the press center to write the news release. In short order, people receiving the issue at the show got the release, and every reporter covering the National had a copy. Crisis averted.

The next day, a silver lining to a decidedly cloudy situation emerged. USA Today ran a story on the phony autograph. And the old saying that there is no such thing as bad publicity? It turned out to be true. Our mistake made the McGwire issue an instant collector’s item. Sales through newsstands and hobby shops soared; the September 1998 Tuff Stuff became the best-selling issue of the year.

Ironic postscript: Turns out, during his record-breaking season, McGwire was taking androstenedione, an over-the-counter muscle enhancement product. It had been banned by the NFL, the World Anti-Doping Agency and the International Olympic Committee, but the substance was not prohibited by Major League Baseball at the time. In 2010, McGwire admitted that he had been using steroids on and off for 10 years, although he claimed he took them for his health, not to help him hit home runs.

McGwire retired in 2001 and became eligible for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007. But, tarnished by his steroid use, he failed to win selection to Cooperstown 10 years in a row. Evidently, the baseball writers who vote for Hall-of-Famers concluded that, just like the autograph on that cover of Tuff Stuff, McGwire was a fake.